ERDC/CHL CHETN-IV-61

December 2003

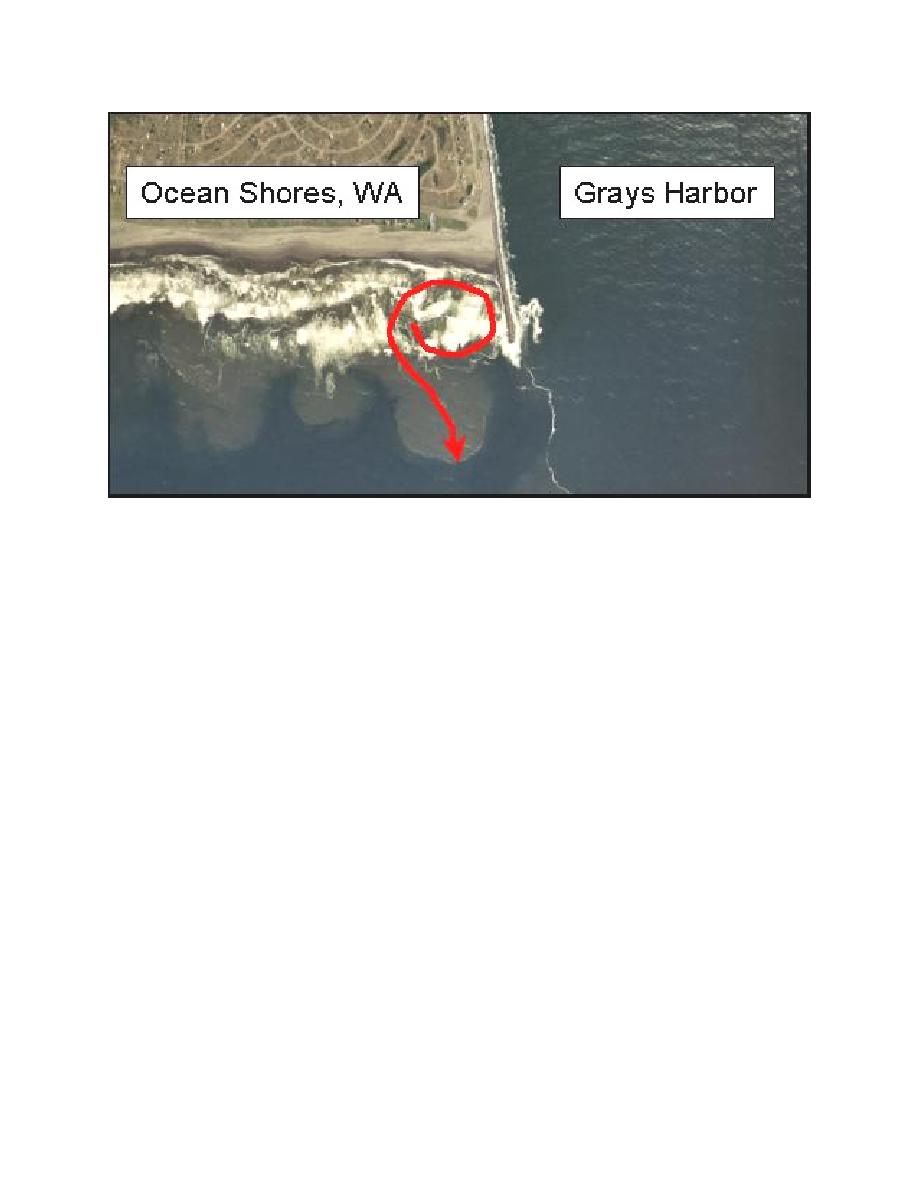

Figure 7. Bathymetric control of waves creating counterclockwise circulation near Grays Harbor north jetty

SPUR JETTY DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS: Governing factors for spur design are location

along the jetty, spur elevation, spur length, distance from the shore, beach slope, water depth,

length, angle with structure, crest elevation, if submerged or emergent, width of crest if sub-

merged or overtopped, and wave climate.

Spur Location. As noted from Table 1, existing spurs have been placed from about 60 percent

of the jetty length from the shoreline to 100 percent, with 75 percent typical. This location will

depend on local conditions near the jetty, such as bottom slope, wave climate, and proximity of

the shoreline. These will determine where waves are breaking and where sediment transport will

be greatest. For short jetties or a flat bottom slope, wave breaking can occur seaward of a jetty

system and sediment transport will be strongest in many cases at the location of the breaker. A

spur may not be as useful if this situation is frequent, as there is small frequency to inter-

cept/divert sediment pathways. Figure 6 shows typical bottom slopes along the U.S. coasts near

inlet structures.

Spur Elevation. Spur elevation might typically be expected to be similar to the jetty it is at-

tached to. Dependent on wave climate, the spur can serve as a fishing platform if access is pro-

vided. The Fort Pierce spur has an asphalt walkway. This may be seen at:

merged spurs have been proposed (Grays Harbor). A reef-type spur was examined in the labora-

tory (discussed later) and may provide similar benefits as a surface-piercing spur, yet is less

costly.

Spur Length. A spur should be long enough to promote a diversion of flow from along the

jetty to keep sediment in the nearshore area rather than move offshore towards the jetty tip. Some

7

Previous Page

Previous Page