Live-bed scour occurs when the bed material upstream of the crossing is moving and moves

as contact sediment discharge in the contracted bridge opening and/or into the local scour

holes.

Typical clear-water scour situations include (1) coarse bed material streams, (2) flat gradient

streams during low flow, (3) local deposits of larger bed materials that are larger than the

biggest fraction being transported by the flow (rock riprap is a special case of this situation),

(4) armored stream beds where the only locations that tractive forces are adequate to

penetrate the armor layer are at piers and/or abutments, (5) vegetated channels where,

again, the only locations that the cover is penetrated is at piers and/or abutments, and (6)

streams with fine bed material and large velocity or shear stress whereby the bed material in

transport washes through a contraction or local scour hole

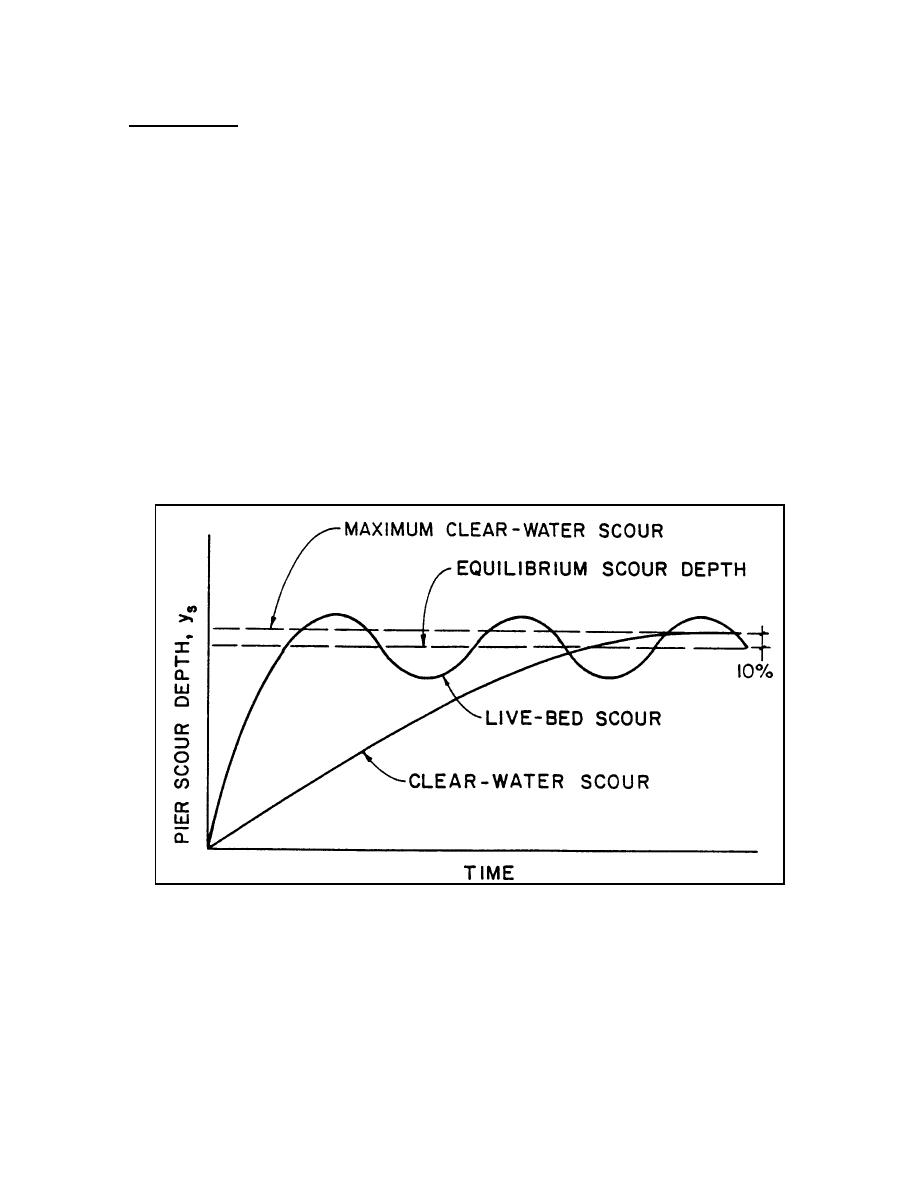

Clear-water scour reaches its maximum over a longer period of time than live-bed scour

(Figure 7.2). This is because clear-water scour occurs mainly on coarse bed material streams.

In fact, clear-water scour may not reach its maximum until after several floods. Also, maximum

clear-water scour is about 10 percent greater than the equilibrium live-bed scour. Bridges over

coarse bed material streams often have clear-water scour at the lower part of a hydrograph,

live-bed scour at the higher discharges, and then clear-water scour on the falling stages.

Figure 7.2. Local scour depth at a pier as a function of time.

Live-bed scour in sand bed streams with a dune bed configuration fluctuates about an

equilibrium scour depth (Figure 7.2). The reason for this is the fluctuating nature of the

sediment transport of the bed material in the approaching flow when the bed configuration of

the stream is dunes. In this case (dune bed configuration in the channel upstream of the

bridge), maximum depth of scour is about 30 percent larger than equilibrium depth of scour.

7.5

Previous Page

Previous Page